QueueSpec: Drafting While You Wait

Abstract

Speculative decoding speeds up LLM generation by letting a system propose several “draft” tokens at once, and then having the target model verify them in a single forward pass. The usual question is: where do we get good drafts cheaply? In this post, we explore queue speculation (QueueSpec): draft tokens come from a smaller model that runs while a request is queuing, so verification can start immediately once the request is serviced. At doubleword we use speculative decoding techniques like this and other throughput-specific optimizations to deliver cheaper inference at scale, by sacrificing end to end latency. If you want to get started with some free credits sign up here: Doubleword Platform

Bottlenecks of Batched Inference

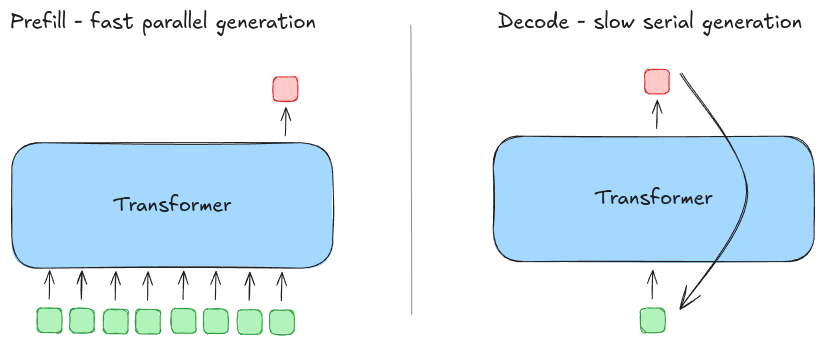

High-throughput inference is mostly a fight against the serial nature of decoding. Prefill can be heavily batched and parallelized, but decoding is a long chain of “one token depends on the last token,” which makes it harder to fully utilize modern GPUs. Speculation is one of the few knobs that can turn that serial loop back into something partially parallel.

If you are optimizing LLM serving, you learn a basic lesson quickly: prefill is fast (and cheap), decode is slow (and expensive).

Even when prompts are long, the prefill phase is a single (or a few) dense forward passes over many tokens. In contrast, decoding is a loop of forward passes—one per output token—where latency stacks up and batching opportunities are limited by KV cache pressure.

Figure 1: Prefill is a burst of parallel work; decoding is a long serial loop of many small steps.

Figure 1: Prefill is a burst of parallel work; decoding is a long serial loop of many small steps.

That “many small steps” reality is why speculative decoding is so attractive: it converts N decode steps into something closer to N/k steps when you can reliably verify k draft tokens per target forward pass.

Speculative decoding in one page

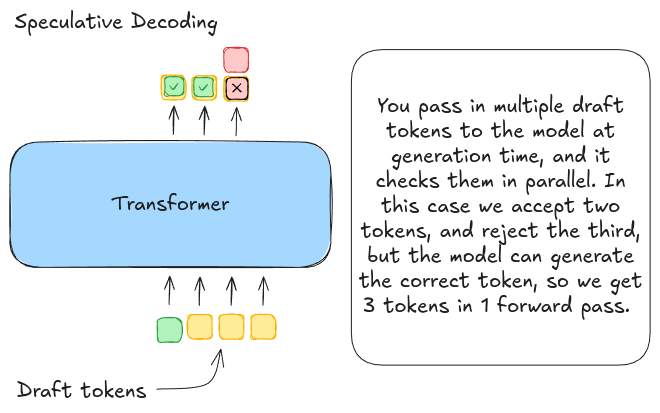

Speculative decoding works like this:

- A draft generator proposes a short continuation of length k (a block of tokens).

- The target model runs one forward pass that verifies those k tokens.

- You accept the longest prefix that matches what the target would have produced, and then repeat.

If you can routinely accept 3–5 tokens at a time, you can get meaningful speedups without changing the target model.

Figure 2: Speculative decoding: draft tokens are proposed, then verified by the target model in a single pass.

Two practical notes that matter in production:

- What you care about is accepted tokens per target forward pass.

- A draft that is cheap but low-quality can be worse than no draft at all: it burns verification work without skipping decode steps.

The real question: where do draft tokens come from?

The speculative decoding literature (and production systems) mostly differ in how they source drafts. Three popular families of draft sources are:

- Small draft model: the original approach—run a smaller model cheaply and verify with the larger model.

- Adapters / MTP / EAGLE-style predictors: predict future tokens from the target model’s hidden state with a small trained adapter.

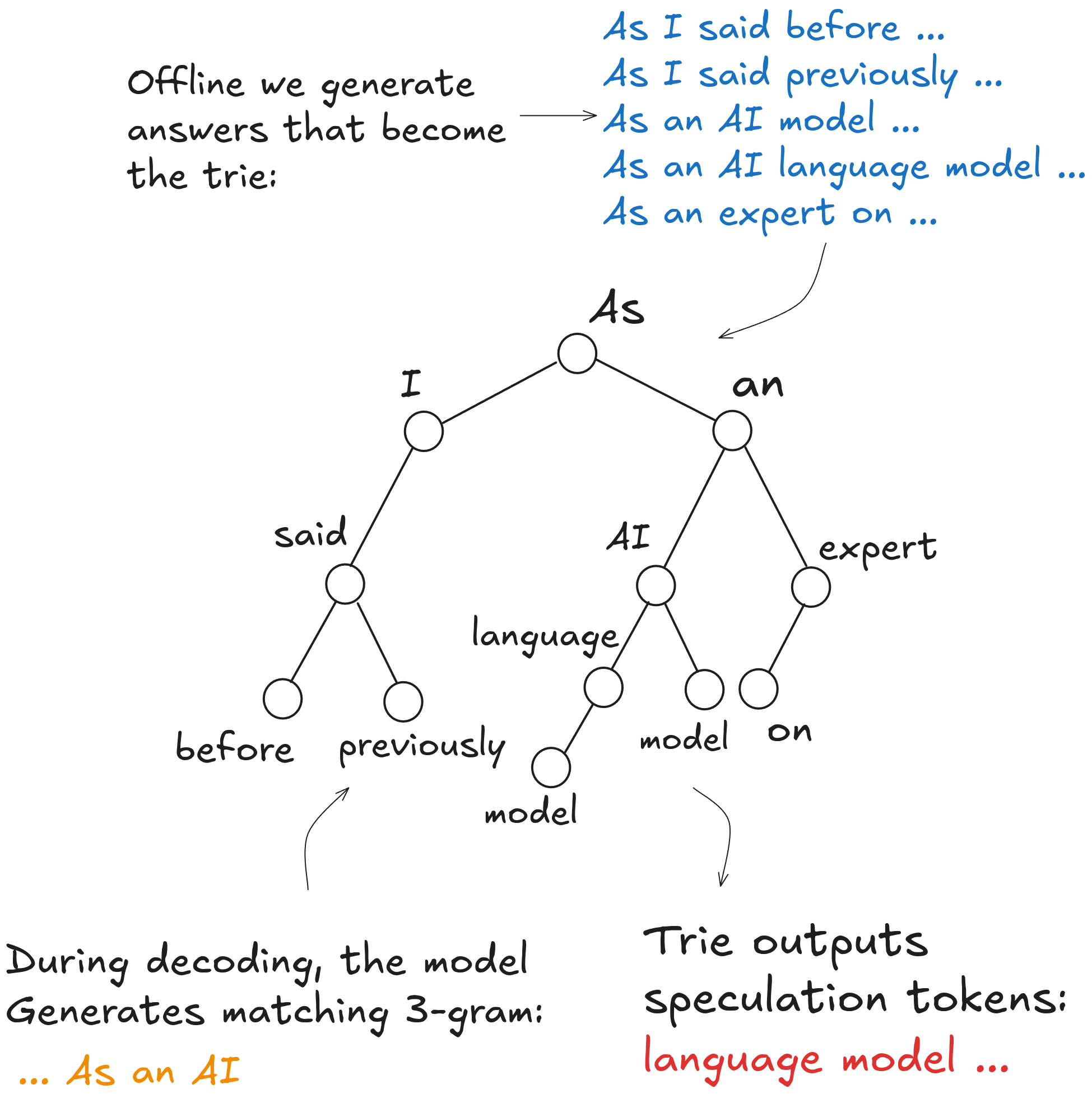

- N-gram Approaches: match generated n-grams against a corpus of text compressed to a prefix trie, and use the trie completions as speculative tokens. Previous work has included compressing datasets into a prefix trie, turning the prompt itself into a prefix trie, or using the previous outputs of the large model (work previously done at Doubleword).

This post is about that last bucket: this bucket is appealing because it is the most general purpose. You don't need model specific adapters or small draft models that dont always exist. When a model is available, this family of speculation techniques will work on day 0 without any work.

Figure 3: n-gram decoding methods work by populating prefix tries with text and when a model generates a matching n-gram from the prefix trie, you use the completions of that branch to speculate from.

Figure 3: n-gram decoding methods work by populating prefix tries with text and when a model generates a matching n-gram from the prefix trie, you use the completions of that branch to speculate from.

QueueSpec: drafting while you wait

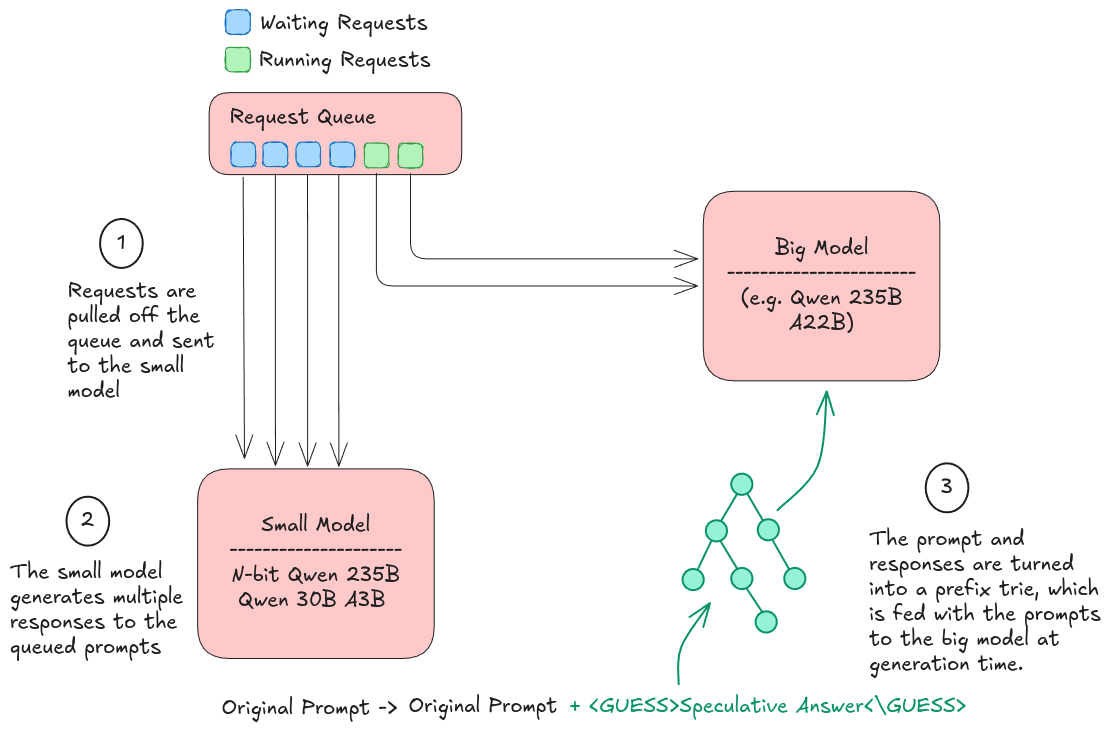

Classic speculative decoding assumes you have a draft model running in the critical path: you start generation, the draft model proposes tokens, and the target model verifies them.

QueueSpec is the queueing-aware variant: it exploits the fact that batched inference systems almost always have a wait state.

When a request arrives, it typically sits in a queue while the server is waiting on KV cache capacity. During that otherwise-idle window, we run a small draft model to produce a candidate continuation.

By the time the request reaches the front of the queue and we actually execute the expensive target model decode loop, we already have draft tokens “buffered” and ready to be verified.

Concretely:

- On enqueue: run a small model to generate n completions of the prompt.

- On service: the scheduler takes the prompt and the proposed answers and constructs a prefix trie of the tokens, which can efficiently identify n-gram matches and generate continuations in the critical path.

- During generation: When the model generates any tokens it is checked against the trie and if there is a match the continuations are extracted and used for speculation.

The key idea is that the draft compute is overlapped with queueing time, not overlapped with the target model’s compute. If the queueing delay is long enough, the draft can be “free” from the system's perspective.

Figure 4: QueueSpec: a small model drafts during queueing time; the target model later verifies those tokens when the request is serviced.

Figure 4: QueueSpec: a small model drafts during queueing time; the target model later verifies those tokens when the request is serviced.

Why this could plausibly work

Two properties of production workloads make this overlap real:

- There is almost always slack: batching, scheduling, and memory pressure create queueing time, especially at high throughput.

- We have good drafters available: quantized versions of big models can run much more cheaply, and even after aggressive quantization, respond in similar ways to their unquantized cousins.

QueueSpec Visualization

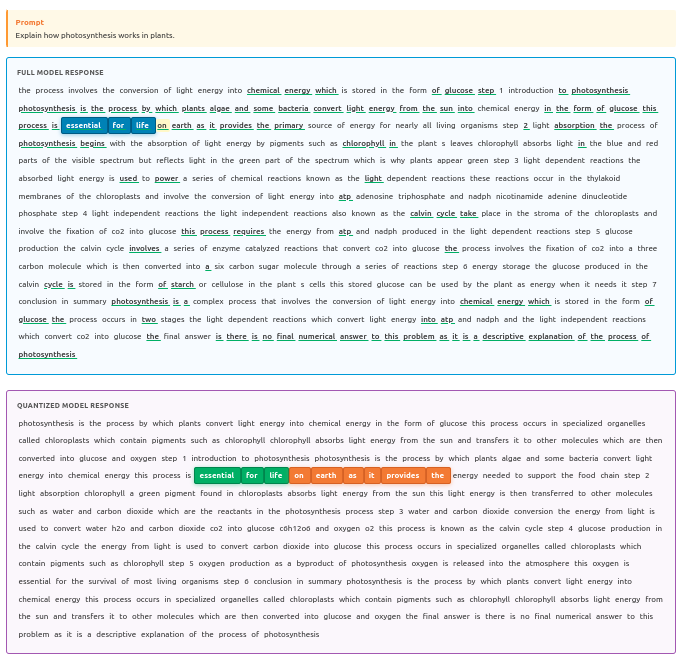

We built a small visualizer that lets you hover over a word in a model response and see where the same preceding n-gram occurs in a draft (here represented as a quantized/alternate response) and how far the continuation agrees.

Figure 5: N-gram visualizer: highlight a local context in the target output and the best matching continuation in the draft text.

Figure 5: N-gram visualizer: highlight a local context in the target output and the best matching continuation in the draft text.

The key pattern you see again and again is:

- Many contexts do have matches but

- The continuation match lengths vary quite a lot: most are short, a few are long.

Most draft texts on the same prompt has some overlap, but the question is if this overlap is enough to create a real speedup.

Results: match rates, overlap length, and speedup

We do all experiments using the Spec-Bench dataset - a dataset designed to test speculative decoding methods, and the Qwen3-VL-30B-A3B model, available on the Doubleword Platform. The smaller model that we use for sampling is the Intel AutoRound 4-bit Quantized version of the model. We measure the speedups against the number of sampled responses from the smaller model. As we increase the number of responses the more likely we are to get n-gram matches, and find continuations the model can speculate from. There is still the question of how effective these completions are in speeding up the model.

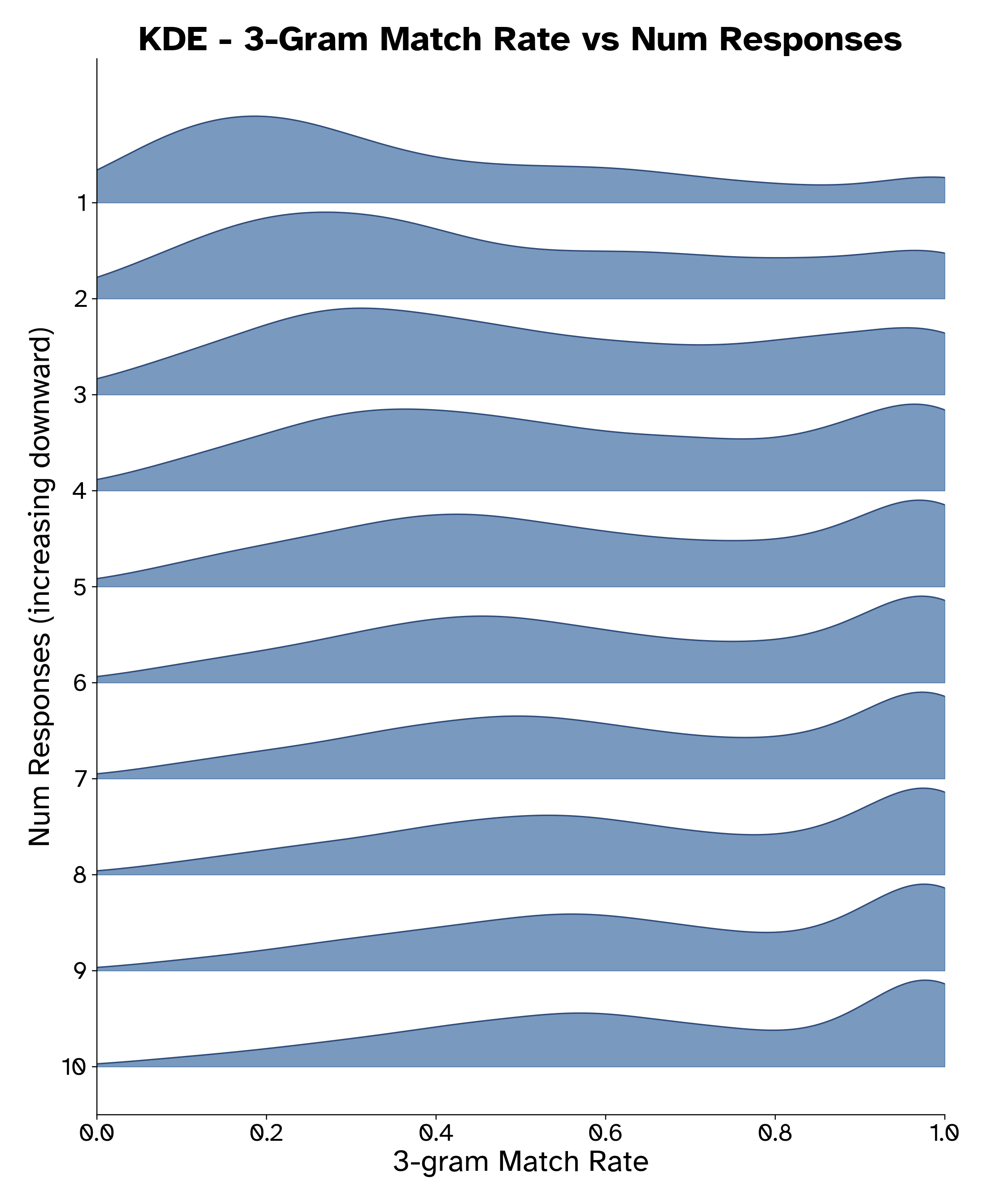

We can summarize the behavior in three plots:

- We get more speculation matches the more completions we use (how often a context has an available continuation)

Figure 6: Distribution of match rates across examples as we increase the number of sampled responses from the draft model. As the number of sampled responses increases we see that the liklihood of n-gram matches grows significantly.

Figure 6: Distribution of match rates across examples as we increase the number of sampled responses from the draft model. As the number of sampled responses increases we see that the liklihood of n-gram matches grows significantly.

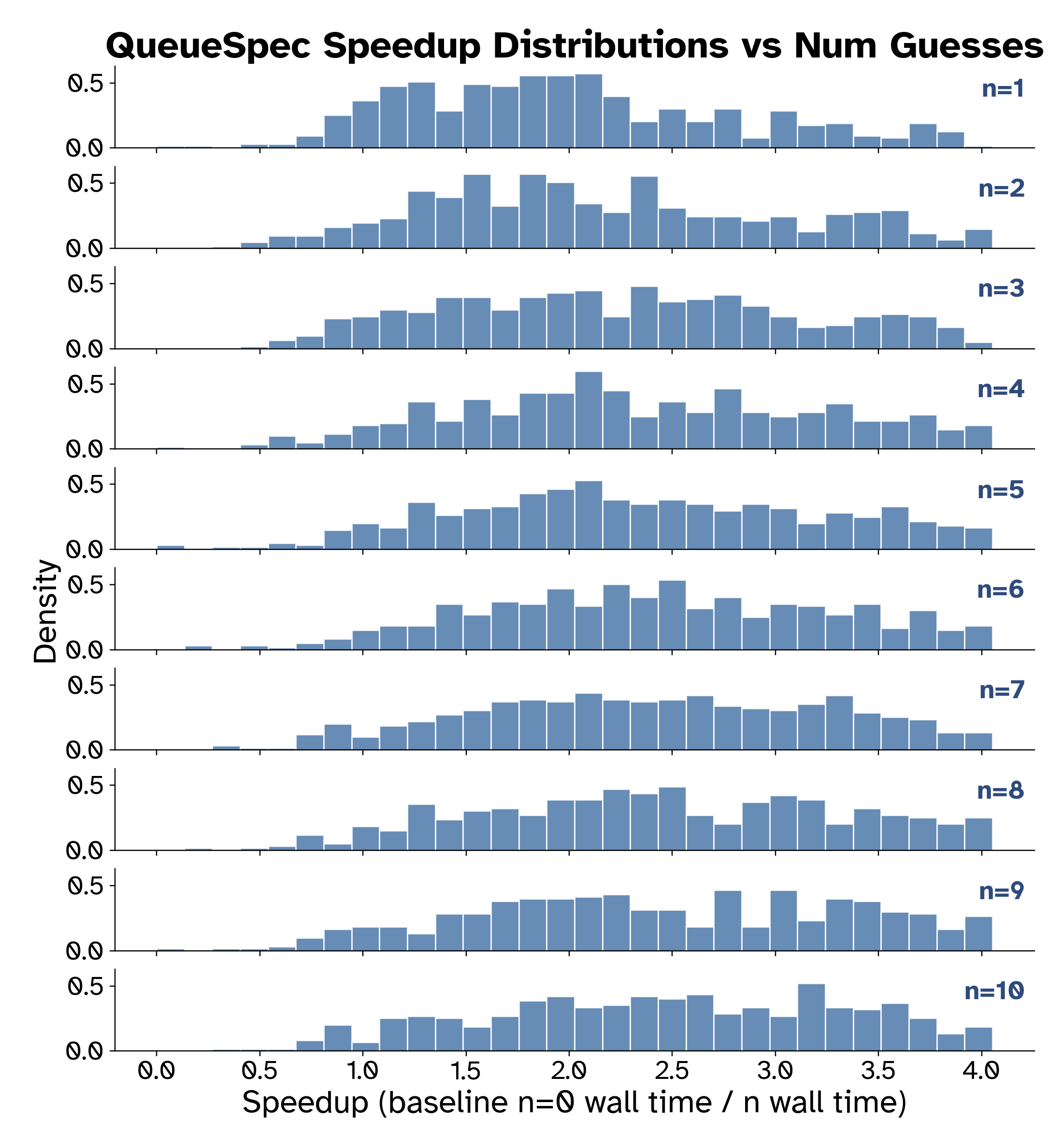

- Speedup distribution skews towards higher speeds as the number of completions increases

Figure 7: Distribution of measured speedups from Queue Speculating compared to the number of sampled responses on the Spec-Bench dataset. .

Figure 7: Distribution of measured speedups from Queue Speculating compared to the number of sampled responses on the Spec-Bench dataset. .

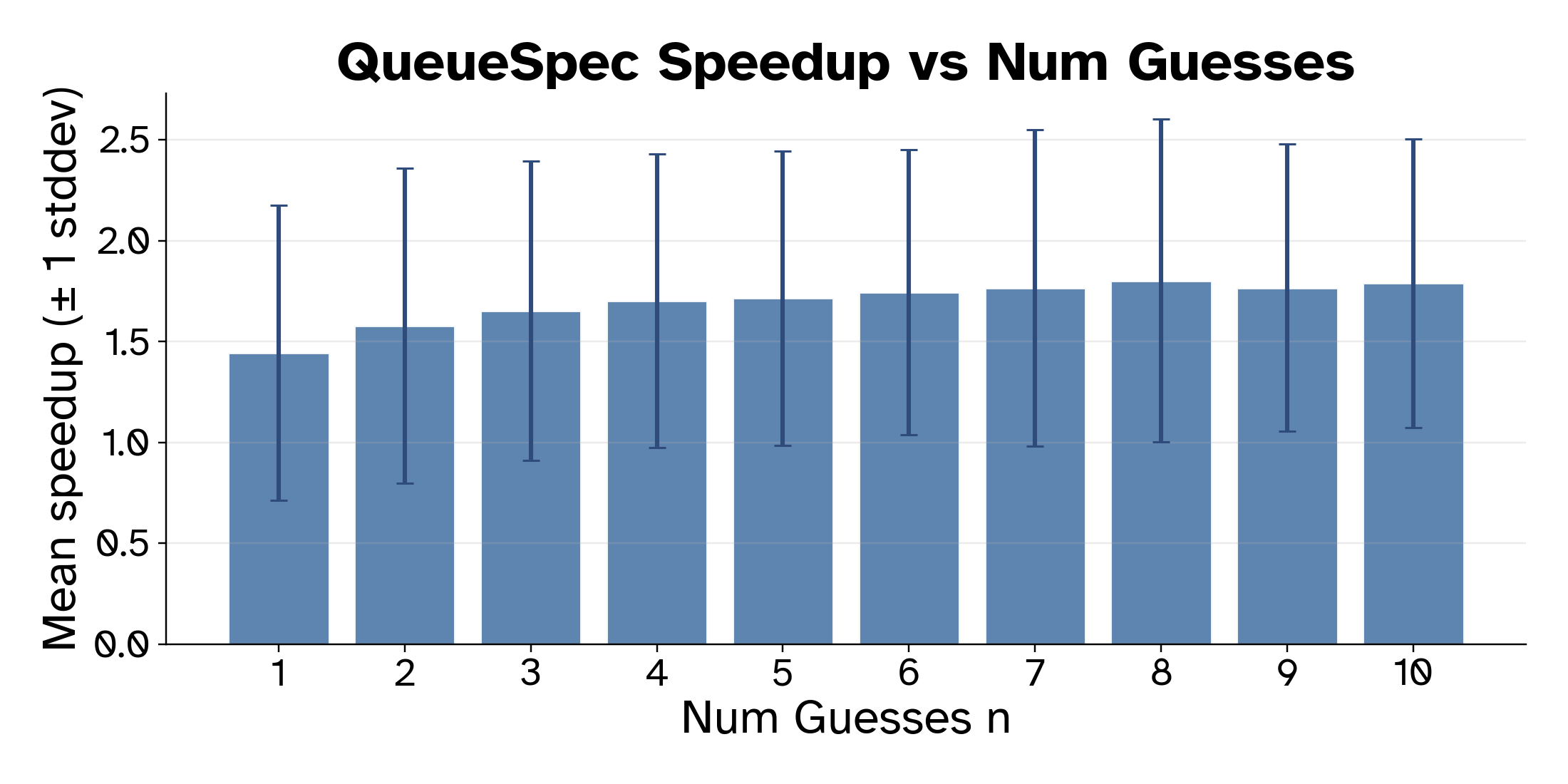

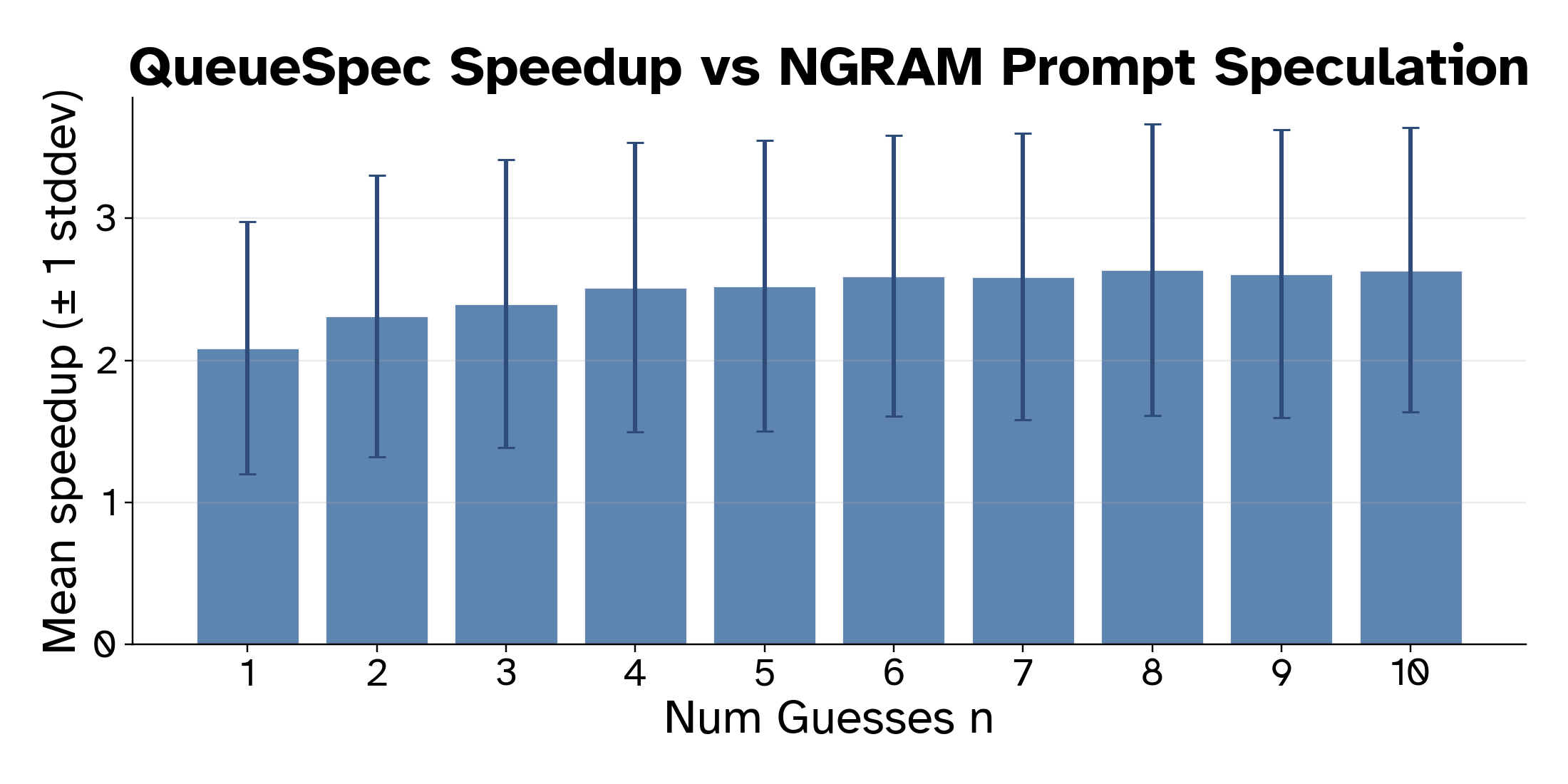

- Speedup Increases as we increase the number of completions

Figure 8: Mean speedup with variability bars vs no speculation as we increase the number of sampled drafts.

Figure 8: Mean speedup with variability bars vs no speculation as we increase the number of sampled drafts.

- We significantly outperform prompt-based n-gram speculation

Figure 9: Speedup of QueueSpec vs Prompt-based NGram Speculation; prompt based speculation is slower than no speculation at all!. Likely because of a poor alignment between prompts and answers in Spec-Bench.

Figure 9: Speedup of QueueSpec vs Prompt-based NGram Speculation; prompt based speculation is slower than no speculation at all!. Likely because of a poor alignment between prompts and answers in Spec-Bench.

Interpreting the results

QueueSpec is significantly more performant than prompt-based ngram decoding, likely because there is much greater alignment in text structure between differing answers than there are between questions and answers. We also see that quantized versions of models retain similar enough structures in their generations to be useful speculation targets for their unquantized cousins models.

You see modest speed improvements as you feed in more guess responses, as you are more likely to find completions the model would have generated.

The great thing about this is that this likely holds for essentially any model that samples discrete outputs, like all transcription models, image to text, or video to text models.

Discussion on cost

There is a an inherent trade off in this form of speculative decoding. We have to pay money to host the small model, and this eats into any savings that we might gain from speculative decoding. We can choose to host a very small model, to decrease the overhead from hosting the speculative model, at the cost of having worse draft tokens that get accepted less often, and dont decrease the serving costs of the target model as much. In the extreme, we could host another copy of the target model, and get nearly perfect drafts, but without decreasing the cost of deployment at all!

In this post we chose a quantized model as the drafter. Cost estimates are hard since the cost of deployment is closely tied to the nature of the deployment. Quantized models in general are much cheaper at decoding - since they require moving 2-4x less memory per forward pass than their unquantized cousins. Since decoding is often the more expensive part of many workloads, and the part of the workload we are trying to optimize, this seems like a good tradeoff.

The best cost outcome would probably come from training a model specifically to create good completions for a target model. You could do this through SFT, or On-policy distillation - or you could directly optimize the construction of good prefix trie's for the model's execution, creating a reward proportional to the number of speculation events that a generated response creates.

Using QueueSpec

If you want to try out QueueSpec yourself you can try out our fork of SGLang. Launch SGLang as normal with --speculative-algorithm NGRAM to initialize the n-gram tree, and then to speculate off of a guess at the end of your prompt send add the following tags: ...<NGRAMGUESS>your guess here </NGRAMGUESS>. The tags and guess will be stripped from the prompt and used to speculate from.

Conclusion

Speculative decoding is one of the most direct ways to claw back throughput from the inherently serial nature of LLM decoding. Most approaches focus on building a better draft model (small models, adapters, future-token predictors), but queue speculation asks a different question: what’s the best draft we can compute while the request is waiting anyway?

The experiments here suggest that you can use significantly cheaper models to draft completions and use n-gram look ups to give significant speedups at runtime without needing token generation in the hot path of the model.